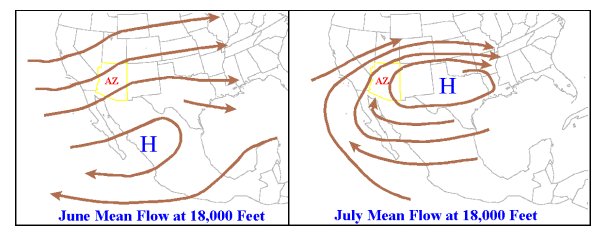

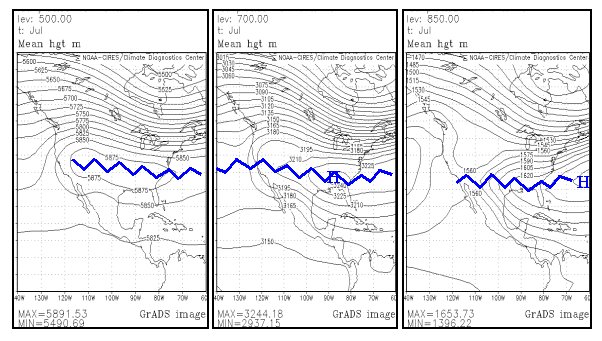

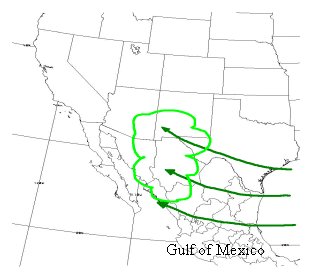

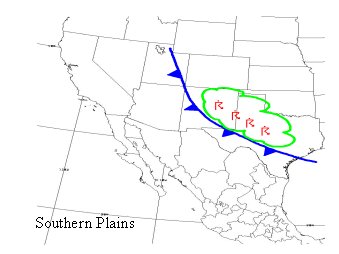

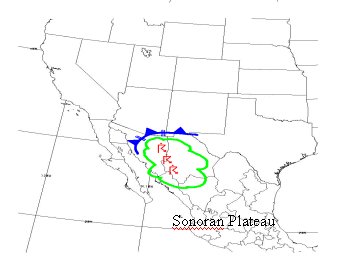

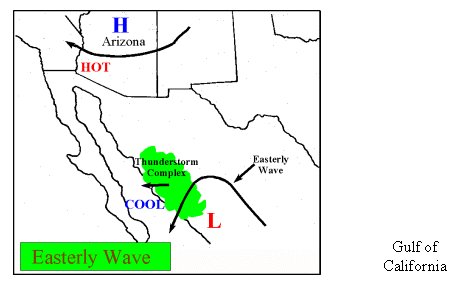

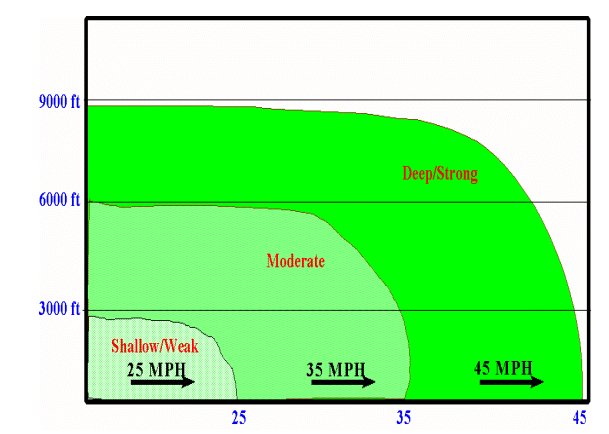

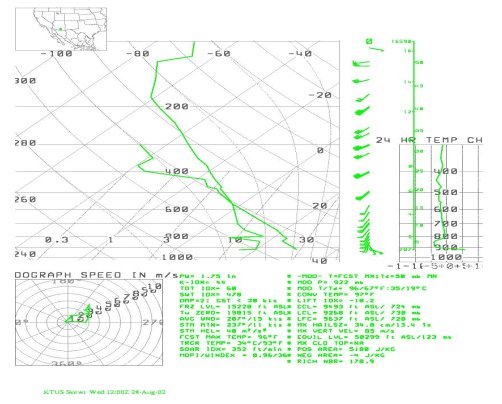

The North American Monsoon typically affects Arizona, New Mexico, Southern California, Utah, and Colorado. For the purpose of this paper, I will focus on Arizona. The North American Monsoon is a regional-scale circulation that develops over southwest North America during the months of July through September. It is associated with a dramatic increase in rainfall that occurs over what is normally an arid region of North America. The NWS officially signifies the start of the monsoon when 3 consecutive days have passed with the dew point above 54 degrees F. Typically the southwest will see airmass thunderstorms develop well before the NWS "official" start of the monsoon season. The monsoon is a seasonal change in upper level winds from the polar westerlies to tropical easterlies and a change from very dry west winds aloft to moist winds aloft from the east or southeast.  The monsoon is an annual occurrence as the sub-tropical ridge shifts poleward during the summer months. As this occurs, the ridge elongates to the west and ushers in warm moist air into the region. A thermal low also sets up over the Desert Southwest due to the intense surface heating providing an optimal pressure gradient from the east-southeast.  The source regions for the moisture influx are the Gulf of Mexico, southern plains, Sonoran Plateau, and the Gulf of California.     The worst days for activity across Arizona occur during a "Gulf Surge". A Gulf of California moisture surge is a low-level influx of moist, relatively cool air that moves northward over the Gulf of California and into Arizona. Surges of moisture from the Gulf of California provide the fuel that feeds the wide spread and intense storms that form across Arizona. A Gulf Surge can occur whenever the surface based thermal low over the southwest intensifies at the same time large thunderstorm complexes are forming over northwest Mexico. Many of the severe and heavy rain producing thunderstorms that form across Arizona during the monsoon are directly related to Gulf of California moisture surges. The most common large-scale pattern observed before a Gulf of California surge is an easterly wave passing over central portions of Mexico at the same time mid-level high pressure and very high surface temperatures are plaguing Arizona. Not all Gulf of California surges are created equal. Some surges are shallow and weak with virtually no affect on Arizona except to increase the humidity. Surges of moderate depth and strength can penetrate all the way into the Mogollon Rim country with a distinct upswing in convective activity across Arizona. Occasionally, maybe once or twice a monsoon season, a strong and deep surge will find its way into Arizona. This is when the real fireworks begin!  As this moisture moves into the southwest, a combination of orographic lift caused by the mountains and intense surface heating causes thunderstorms to develop across the region. The monsoon season typically begins early July when we see east/southeast winds and an increase in moisture aloft. Storms will develop initially over the mountains with some development in the valleys with the rain never reaching the surface (virga). The problem with these dry storms is significant downbursts and dust storms due to evaporational cooling with storm bases around 12,000 feet. By mid-July we begin to see a rapid increase in surface moisture and thunderstorm coverage. In southeast AZ, downbursts become less of a problem as storm bases lower to around 8,000 feet, however; large downburst potential remains high across the Phoenix area. Thunderstorm timing shifts into the early afternoon throughout southeastern AZ and evening hours across Phoenix. By late July-mid August, the flash flood threat across the state is at it peak with storms continuing into the nighttime hours. Microbursts are less common, but large scale downbursts remain a challenge as storms collapse across the region. We do see occasional breaks in thunderstorm activity especially following a very active day. Around late August-early September, we begin to see an increase in number of days between thunderstorm activity. The flash flood threat remains high, especially if tropical cyclones get in the mix. This time of the year the hail and tornado threat increases as cells tend to take on a more supercell-like structure. By late September, we see the easterly flow gradually transition back to the westerlies as the sub-tropical ridge retreats equatorward. The lingering moisture begins to interact with incoming cold fronts as we start the transition to the fall/winter season. The hail and tornado threat is at its peak during this time as cold air starts creeping its way into the region and cut-off lows start to develop off the coast of southern California. Forecasting the onset of the North American Monsoon is not difficult with knowledge of the synoptic-scale pattern. A knowledgeable forecaster can monitor computer models to determine when the atmospheric conditions are in place for the monsoon season to begin. The biggest challenge for forecasters is when the monsoon season is in effect. Powerful winds, lightning, and heavy rains are the biggest challenges forecasters in the southwest face when dealing with thunderstorm development. One of the most useful tools to use is hands down, the skew-T. The skew-T diagram can tip off the seasoned forecaster to impending doom! Looking at the cold (morning) sounding and forecasted soundings throughout the day can give the forecaster clues to see how bad your day is really going to be. Thunderstorms are not likely unless CAPE/unstable LI are present or develop during the day. Thus, the biggest challenge in estimating a reasonable lifted index and/or CAPE for Arizona locations is correctly forecasting the afternoon depth, temperature, and moisture profile of the boundary layer. Here's an example of a really busy day! A 1200Z sounding with a CAPE value of 5180 j/kg and LI of -10.2:  Arizona forecasters face numerous challenges during the monsoon season. However, armed with a strong working knowledge of skew-T, models, and radar the forecaster will be able to warn the public and government sectors to potentially deadly hazards in a timely manner. References: Erik Pytlak, NOAA/NWS Tucson, AZ, "The North American Monsoon: Impacts on the Desert Southwest" National Weather Service Forecast Office Tucson, AZ, "What is the Mexican Monsoon", retrieved 15 Mar 08 http://www.wrh.noaa.gov/twc/monsoon/mexmonsoon.php National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center, "Reports to the Nation: The North American Monsoon", Aug 04 http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/outreach/Report-to-the-Nation-Monsoon_aug04.pdf Wikipedia, "Monsoon", retrieved 15 Mar 08 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monsoon |