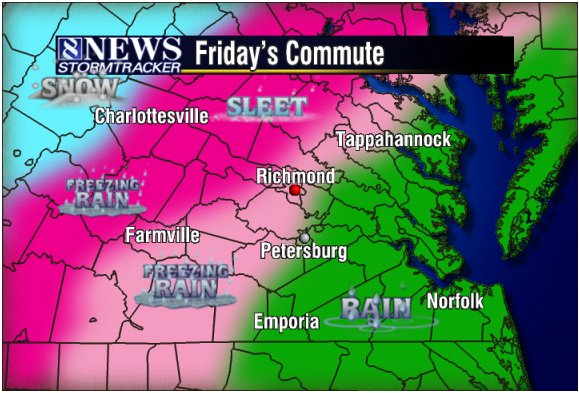

Weather is similar to real estate: It's all about location. Central Virginia has an interesting setup that allows for a tremendous variety in weather events; Richmond, the capital city, is located roughly 75 miles west of Chesapeake Bay, which connects with the Atlantic Ocean, and roughly 100 miles east from the Blue Ridge Mountains, part of the Appalachian chain. These are two very powerful weather controls, buoyed by the fact that the state sits between 36 and 39 degrees North latitude. Virginia is quite often the buffer zone between winter weather events moving along the Polar Jet to the north, and warm-weather events moving along the Subtropical Jet. This recipe, then, presents interesting scenarios in the forecasting of winter precipitation, which often times includes sleet and freezing rain. The Richmond region can be the transition zone between snow to the north and west and rain to the south and east, and it's not uncommon for that zone to be marked with sleet and freezing rain. In its most extreme form, Central Virginia can play host to large ice storms, including the memorable "Christmas Ice Storm," which struck the region on December 23, 1998 and lasted through the Christmas holiday. According to records from the Virginia Department of Emergency Management, ice accumulations of more than an inch caused downed trees and power lines, and more than 400,000 people were without power on Christmas Eve. This kind of aftermath puts a lot of pressure on forecasters to correctly predict the type of precipitation that will come with winter weather. Precipitation type is determined by the air masses in place and the thickness of those air masses. Sleet is the result of snow that partially melts through an elevated warm layer then re-freezes upon entering colder air near the surface. Freezing rain also begins its life as snow, but fully melts in the elevated warm layer, re-freezing upon hitting a sub-freezing surface. Meteorologist Matt DiNardo, who has forecasted in the area several years for radio and television, says the risk of freezing rain and sleet usually presents itself around six to eight times a season; because Central Virginia's winter season is a relatively short one, that can translate to once every two weeks. So what are the atmospheric and orographic processes that make the area so prone to seeing ice? The National Weather Service office in Wakefield, which forecasts for the central and southeastern portions of the state, has pin-pointed six separate winter storm types that tend to affect Central Virginia, and one of them focuses on icy precipitation. The prevalent ice set-up as diagramed by the Wakefield forecasters includes strong high pressure and an arctic air mass north of the polar jet that moves to the south and southeast. The surface cold front pushes southeast slowly, across the Ohio valley and toward Virginia. Meanwhile, a series of upper-level systems move along the warmer subtropical jet and toward the northeast. The resulting warmer, moist air moves in toward the southeastern portion of the state, and begins overrunning the dense, cold air that is moving in from the opposite direction. This, of course, leads to precipitation in the upper levels of the atmosphere that begins as snow, melts as it passes through the warmer air brought along by the subtropical jet, and begins to re-freeze in the arctic air toward the surface. That is an overview of the synoptic setup, but the key to the precipitation type truly lies in the mesoscale influences, which include the orographic factors. Cold air damming is a frequent feature of winter weather in Central Virginia. Cold air draining down from the north is trapped in by the mountains to the west of the Richmond region, confining that air just west of the I-95 corridor. Warm air then lifts in from the south and overruns the cold air, leading to a wintry mix. There's a drastic elevation change that's also a big factor - remember, Central Virginia is a transition zone between the upper Appalachians and the Atlantic ocean; in fact the city of Richmond sits directly on what's known as the Fall Line, a zone of change between the rocky Piedmont plateau and the flat Coastal Plain. This elevation change also plays a critical factor in the transition between snow, sleet, freezing rain, and rain. That common transition across Central Virginia, from northwest to southeast, can be easy to visualize. In the western section of the forecast area, closer to the mountains, the cold air mass is much thicker, already having drained in from the north and being dammed in, making snow much more likely in this area. But the colder air is shallower closer to the mild coastal waters. The southeastern tip, including the city of Norfolk, is under the stronger influence of the warmer, subtropical air, often keeping the precipitation there as rain. Figure 1 is an example of this change, and is a winter precipitation forecast from Friday, February 22nd, 2008.  One of my first experiences forecasting sleet and freezing rain came on February 22nd, and was a good lesson in the difference just one or two degrees can make. Rain was falling in metro Richmond in the very early hours of that Friday, with temperatures hovering right around the freezing mark. Coats of ice had quickly formed on cars, railings, and other exposed metal surfaces, but roads through the metro area did not freeze over; this was not the case in some of the counties that surround the city, where rain did freeze on the roadways, causing some traffic hazards. The temperatures in those outlying counties were just a degree or two cooler. Since there's no way to prevent winter precipitation, the question is, how do you best prepare for it? Accurate forecasting is crucial, but can be incredibly tricky. The National Weather Service will issue Winter Weather Advisories for "accumulations of snow, freezing rain, freezing drizzle, and sleet which will cause significant inconveniences and, if caution is not exercised, could lead to life threatening situations." If the predominant precipitation type looks to be freezing rain, the NWS will issue a Freezing Rain Advisory (for a trace of accumulation) or a Warning (0.25" in Central Virginia). The Hydrometeorological Prediction Center's heavy snow and ice discussions are also useful in assessing the probabilities of winter precipitation type. But due to the mesoscale influences, model data can be very inconsistent. Meteorologist DiNardo says FOUS data can be helpful in assessing the vertical layers of the atmosphere and vertical motion during different forecast periods. He also says the advent of BUFKIT (NWS Buffalo's forecast profile visualization tool) had made it easier to forecast winter precipitation by better assessing atmospheric thickness values and wind fields. The wind fields can be prove critical, and often result in a "busted" forecast; if a low-level wind coming from the E/SE is too strong, it will allow too much warm air to flood in close to the surface, this results in an all-rain event. On the other hand, a wind straight out of the west will result in downsloping, which can fill the area with dry, warmer air that can also prevent the freezing of any precipitation (although enough rain falling into dry air will result in some evaporational cooling). Clearly, as with a weather event of any size, local knowledge is the best tool a forecaster has. Drawing from past events can help a forecaster figure out which locations are most likely to see which kinds of precipitation, and can also aid in forecasting the "change-over" times, when the falling sleet/freezing rain will switch to all rain. As stated before with the Christmas storm of 1998, ice on the ground (not to on mention power lines and trees) can have devastating effects on the people who live in Central Virginia. So knowing, and understanding, how and why winter precipitation forms is an important part of forecasting in the region. References: Albright, Wayne: Lead Forecaster, National Weather Service, Wakefield, VA. DiNardo, Matt: Morning Meteorologist, WRIC-TV 8 in Richmond, VA. Grymes, Charles A. "Virginia Places." http://www.virginiaplaces.org/ Haby, Jeff: Professor, Mississippi State University. http://www.theweatherpredction.com Lutgens, Frederick K. and Edward J. Tarbuck. "The Atmosphere: An Introduction to Meteorology." 9th ed. Pages 145-146. National Weather Service, Wakefield, VA office: http://www.erh.noaa.gov/akq/ The Virginia Department of Emergency Management's Newsroom and Archives: http://www.vdem.state.va.us/ Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: http://www.wikipedia.org/ |